Projekttitel: eManual Alte Geschichte

Modul [optional]:

Autor_in: Homer

Lizenz: CC-BY-NC-SA

Hom. Il. 6, 399 – 493

ἥ οἱ ἔπειτ᾽ ἤντησ᾽, ἅμα δ᾽ ἀμφίπολος κίεν αὐτῇ

400 παῖδ᾽ ἐπὶ κόλπῳ ἔχουσ᾽ ἀταλάφρονα νήπιον αὔτως

Ἑκτορίδην ἀγαπητὸν ἀλίγκιον ἀστέρι καλῷ,

τόν ῥ᾽ Ἕκτωρ καλέεσκε Σκαμάνδριον, αὐτὰρ οἱ ἄλλοι

Ἀστυάνακτ᾽: οἶος γὰρ ἐρύετο Ἴλιον Ἕκτωρ.

ἤτοι ὃ μὲν μείδησεν ἰδὼν ἐς παῖδα σιωπῇ:

405 Ἀνδρομάχη δέ οἱ ἄγχι παρίστατο δάκρυ χέουσα,

ἔν τ᾽ ἄρα οἱ φῦ χειρὶ ἔπος τ᾽ ἔφατ᾽ ἔκ τ᾽ ὀνόμαζε:

δαιμόνιε φθίσει σε τὸ σὸν μένος, οὐδ᾽ ἐλεαίρεις

παῖδά τε νηπίαχον καὶ ἔμ᾽ ἄμμορον, ἣ τάχα χήρη

σεῦ ἔσομαι: τάχα γάρ σε κατακτανέουσιν Ἀχαιοὶ

410 πάντες ἐφορμηθέντες: ἐμοὶ δέ κε κέρδιον εἴη

σεῦ ἀφαμαρτούσῃ χθόνα δύμεναι: οὐ γὰρ ἔτ᾽ ἄλλη

ἔσται θαλπωρὴ ἐπεὶ ἂν σύ γε πότμον ἐπίσπῃς

ἀλλ᾽ ἄχε᾽: οὐδέ μοι ἔστι πατὴρ καὶ πότνια μήτηρ.

‘‘ ἤτοι γὰρ πατέρ᾽ ἁμὸν ἀπέκτανε δῖος Ἀχιλλεύς,

415 ἐκ δὲ πόλιν πέρσεν Κιλίκων εὖ ναιετάουσαν

Θήβην ὑψίπυλον: κατὰ δ᾽ ἔκτανεν Ἠετίωνα,

οὐδέ μιν ἐξενάριξε, σεβάσσατο γὰρ τό γε θυμῷ,

ἀλλ᾽ ἄρα μιν κατέκηε σὺν ἔντεσι δαιδαλέοισιν

ἠδ᾽ ἐπὶ σῆμ᾽ ἔχεεν: περὶ δὲ πτελέας ἐφύτευσαν

420 νύμφαι ὀρεστιάδες κοῦραι Διὸς αἰγιόχοιο.

οἳ δέ μοι ἑπτὰ κασίγνητοι ἔσαν ἐν μεγάροισιν

οἳ μὲν πάντες ἰῷ κίον ἤματι Ἄϊδος εἴσω:

πάντας γὰρ κατέπεφνε ποδάρκης δῖος Ἀχιλλεὺς

βουσὶν ἐπ᾽ εἰλιπόδεσσι καὶ ἀργεννῇς ὀΐεσσι.

425 μητέρα δ᾽, ἣ βασίλευεν ὑπὸ Πλάκῳ ὑληέσσῃ,

τὴν ἐπεὶ ἂρ δεῦρ᾽ ἤγαγ᾽ ἅμ᾽ ἄλλοισι κτεάτεσσιν,

ἂψ ὅ γε τὴν ἀπέλυσε λαβὼν ἀπερείσι᾽ ἄποινα,

πατρὸς δ᾽ ἐν μεγάροισι βάλ᾽ Ἄρτεμις ἰοχέαιρα.

Ἕκτορ ἀτὰρ σύ μοί ἐσσι πατὴρ καὶ πότνια μήτηρ

430 ἠδὲ κασίγνητος, σὺ δέ μοι θαλερὸς παρακοίτης:

ἀλλ᾽ ἄγε νῦν ἐλέαιρε καὶ αὐτοῦ μίμν᾽ ἐπὶ πύργῳ,

μὴ παῖδ᾽ ὀρφανικὸν θήῃς χήρην τε γυναῖκα:

λαὸν δὲ στῆσον παρ᾽ ἐρινεόν, ἔνθα μάλιστα

ἀμβατός ἐστι πόλις καὶ ἐπίδρομον ἔπλετο τεῖχος.

435 τρὶς γὰρ τῇ γ᾽ ἐλθόντες ἐπειρήσανθ᾽ οἱ ἄριστοι

ἀμφ᾽ Αἴαντε δύω καὶ ἀγακλυτὸν Ἰδομενῆα

ἠδ᾽ ἀμφ᾽ Ἀτρεΐδας καὶ Τυδέος ἄλκιμον υἱόν:

ἤ πού τίς σφιν ἔνισπε θεοπροπίων ἐῢ εἰδώς,

ἤ νυ καὶ αὐτῶν θυμὸς ἐποτρύνει καὶ ἀνώγει.

440 τὴν δ᾽ αὖτε προσέειπε μέγας κορυθαίολος Ἕκτωρ:

‘ἦ καὶ ἐμοὶ τάδε πάντα μέλει γύναι: ἀλλὰ μάλ᾽ αἰνῶς

αἰδέομαι Τρῶας καὶ Τρῳάδας ἑλκεσιπέπλους,

αἴ κε κακὸς ὣς νόσφιν ἀλυσκάζω πολέμοιο:

οὐδέ με θυμὸς ἄνωγεν, ἐπεὶ μάθον ἔμμεναι ἐσθλὸς

445 αἰεὶ καὶ πρώτοισι μετὰ Τρώεσσι μάχεσθαι

ἀρνύμενος πατρός τε μέγα κλέος ἠδ᾽ ἐμὸν αὐτοῦ.

εὖ γὰρ ἐγὼ τόδε οἶδα κατὰ φρένα καὶ κατὰ θυμόν:

ἔσσεται ἦμαρ ὅτ᾽ ἄν ποτ᾽ ὀλώλῃ Ἴλιος ἱρὴ

καὶ Πρίαμος καὶ λαὸς ἐϋμμελίω Πριάμοιο.

450 ἀλλ᾽ οὔ μοι Τρώων τόσσον μέλει ἄλγος ὀπίσσω,

οὔτ᾽ αὐτῆς Ἑκάβης οὔτε Πριάμοιο ἄνακτος

οὔτε κασιγνήτων, οἵ κεν πολέες τε καὶ ἐσθλοὶ

ἐν κονίῃσι πέσοιεν ὑπ᾽ ἀνδράσι δυσμενέεσσιν,

ὅσσον σεῦ, ὅτε κέν τις Ἀχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων

455 δακρυόεσσαν ἄγηται ἐλεύθερον ἦμαρ ἀπούρας:

καί κεν ἐν Ἄργει ἐοῦσα πρὸς ἄλλης ἱστὸν ὑφαίνοις,

καί κεν ὕδωρ φορέοις Μεσσηΐδος ἢ Ὑπερείης

πόλλ᾽ ἀεκαζομένη, κρατερὴ δ᾽ ἐπικείσετ᾽ ἀνάγκη:

καί ποτέ τις εἴπῃσιν ἰδὼν κατὰ δάκρυ χέουσαν:

460 Ἕκτορος ἥδε γυνὴ ὃς ἀριστεύεσκε μάχεσθαι

Τρώων ἱπποδάμων ὅτε Ἴλιον ἀμφεμάχοντο.

ὥς ποτέ τις ἐρέει: σοὶ δ᾽ αὖ νέον ἔσσεται ἄλγος

χήτεϊ τοιοῦδ᾽ ἀνδρὸς ἀμύνειν δούλιον ἦμαρ.

ἀλλά με τεθνηῶτα χυτὴ κατὰ γαῖα καλύπτοι

465 πρίν γέ τι σῆς τε βοῆς σοῦ θ᾽ ἑλκηθμοῖο πυθέσθαι.

ὣς εἰπὼν οὗ παιδὸς ὀρέξατο φαίδιμος Ἕκτωρ:

ἂψ δ᾽ ὃ πάϊς πρὸς κόλπον ἐϋζώνοιο τιθήνης

ἐκλίνθη ἰάχων πατρὸς φίλου ὄψιν ἀτυχθεὶς

ταρβήσας χαλκόν τε ἰδὲ λόφον ἱππιοχαίτην,

470δεινὸν ἀπ᾽ ἀκροτάτης κόρυθος νεύοντα νοήσας.

ἐκ δ᾽ ἐγέλασσε πατήρ τε φίλος καὶ πότνια μήτηρ:

αὐτίκ᾽ ἀπὸ κρατὸς κόρυθ᾽ εἵλετο φαίδιμος Ἕκτωρ,

καὶ τὴν μὲν κατέθηκεν ἐπὶ χθονὶ παμφανόωσαν:

αὐτὰρ ὅ γ᾽ ὃν φίλον υἱὸν ἐπεὶ κύσε πῆλέ τε χερσὶν

475εἶπε δ᾽ ἐπευξάμενος Διί τ᾽ ἄλλοισίν τε θεοῖσι:

Ζεῦ ἄλλοι τε θεοὶ δότε δὴ καὶ τόνδε γενέσθαι

παῖδ᾽ ἐμὸν ὡς καὶ ἐγώ περ ἀριπρεπέα Τρώεσσιν,

ὧδε βίην τ᾽ ἀγαθόν, καὶ Ἰλίου ἶφι ἀνάσσειν:

καί ποτέ τις εἴποι πατρός γ᾽ ὅδε πολλὸν ἀμείνων

480ἐκ πολέμου ἀνιόντα: φέροι δ᾽ ἔναρα βροτόεντα

κτείνας δήϊον ἄνδρα, χαρείη δὲ φρένα μήτηρ.’

ὣς εἰπὼν ἀλόχοιο φίλης ἐν χερσὶν ἔθηκε

παῖδ᾽ ἑόν: ἣ δ᾽ ἄρα μιν κηώδεϊ δέξατο κόλπῳ

δακρυόεν γελάσασα: πόσις δ᾽ ἐλέησε νοήσας,

485 χειρί τέ μιν κατέρεξεν ἔπος τ᾽ ἔφατ᾽ ἔκ τ᾽ ὀνόμαζε:

δαιμονίη μή μοί τι λίην ἀκαχίζεο θυμῷ:

οὐ γάρ τίς μ᾽ ὑπὲρ αἶσαν ἀνὴρ Ἄϊδι προϊάψει:

μοῖραν δ᾽ οὔ τινά φημι πεφυγμένον ἔμμεναι ἀνδρῶν,

οὐ κακὸν οὐδὲ μὲν ἐσθλόν, ἐπὴν τὰ πρῶτα γένηται.

490 ἀλλ᾽ εἰς οἶκον ἰοῦσα τὰ σ᾽ αὐτῆς ἔργα κόμιζε

ἱστόν τ᾽ ἠλακάτην τε, καὶ ἀμφιπόλοισι κέλευε

ἔργον ἐποίχεσθαι: πόλεμος δ᾽ ἄνδρεσσι μελήσει

πᾶσι, μάλιστα δ᾽ ἐμοί, τοὶ Ἰλίῳ ἐγγεγάασιν.’

Projekttitel: eManual Alte Geschichte

Modul [optional]:

Übersetzung: A.T. Murray

Lizenz: CC-BY-NC-SA

Übersetzung

She [Andromache] now met him, and with her came a handmaid bearing in her bosom [400] the tender boy, a mere babe, the well-loved son of Hector, like to a fair star. Him Hector was wont to call Scamandrius, but other men Astyanax; for only Hector guarded Ilios.1 Then Hector smiled, as he glanced at his boy in silence, [405] but Andromache came close to his side weeping, and clasped his hand and spake to him, saying:“Ah, my husband, this prowess of thine will be thy doom, neither hast thou any pity for thine infant child nor for hapless me that soon shall be thy widow; for soon will the Achaeans [410] all set upon thee and slay thee. But for me it were better to go down to the grave if I lose thee, for nevermore shall any comfort be mine, when thou hast met thy fate, but only woes. Neither father have I nor queenly mother. ” “ My father verily goodly Achilles slew, [415] for utterly laid he waste the well-peopled city of the Cilicians, even Thebe of lofty gates. He slew Eëtion, yet he despoiled him not, for his soul had awe of that; but he burnt him in his armour, richly dight, and heaped over him a barrow; and all about were elm-trees planted by nymphs of the mountain, daughters of Zeus that beareth the aegis. [420] And the seven brothers that were mine in our halls, all these on the selfsame day entered into the house of Hades, for all were slain of swift-footed, goodly Achilles, amid their kine of shambling gait and their white-fleeced sheep. [425] And my mother, that was queen beneath wooded Placus, her brought he hither with the rest of the spoil, but thereafter set her free, when he had taken ransom past counting; and in her father’s halls Artemis the archer slew her. Nay, Hector, thou art to me father and queenly mother, [430] thou art brother, and thou art my stalwart husband. Come now, have pity, and remain here on the wall, lest thou make thy child an orphan and thy wife a widow. And for thy host, stay it by the wild fig-tree, where the city may best be scaled, and the wall is open to assault. [435] For thrice at this point came the most valiant in company with the twain Aiantes and glorious Idomeneus and the sons of Atreus and the valiant son of Tydeus, and made essay to enter: whether it be that one well-skilled in soothsaying told them, or haply their own spirit urgeth and biddeth them thereto.” [440] Then spake to her great Hector of the flashing helm: “Woman, I too take thought of all this, but wondrously have I shame of the Trojans, and the Trojans‘ wives, with trailing robes, if like a coward I skulk apart from the battle. Nor doth mine own heart suffer it, seeing I have learnt to be valiant [445] always and to fight amid the foremost Trojans, striving to win my father’s great glory and mine own. For of a surety know I this in heart and soul: the day shall come when sacred Ilios shall be laid low, and Priam, and the people of Priam with goodly spear of ash. [450] Yet not so much doth the grief of the Trojans that shall be in the aftertime move me, neither Hecabe’s own, nor king Priam’s, nor my brethren’s, many and brave, who then shall fall in the dust beneath the hands of their foemen, as doth thy grief, when some brazen-coated Achaean [455] shall lead thee away weeping and rob thee of thy day of freedom. Then haply in Argos shalt thou ply the loom at another s bidding, or bear water from Messeis or Hypereia, sorely against thy will, and strong necessity shall be laid upon thee. And some man shall say as he beholdeth thee weeping: [460] “Lo, the wife of Hector, that was pre-eminent in war above all the horse-taming Trojans, in the day when men fought about Ilios.” So shall one say; and to thee shall come fresh grief in thy lack of a man like me to ward off the day of bondage. But let me be dead, and let the heaped-up earth cover me, [465] ere I hear thy cries as they hale thee into captivity.” So saying, glorious Hector stretched out his arms to his boy, but back into the bosom of his fair-girdled nurse shrank the child crying, affrighted at the aspect of his dear father, and seized with dread of the bronze and the crest of horse-hair, [470] as he marked it waving dreadfully from the topmost helm. Aloud then laughed his dear father and queenly mother; and forthwith glorious Hector took the helm from his head and laid it all-gleaming upon the ground. But he kissed his dear son, and fondled him in his arms, [475] and spake in prayer to Zeus and the other gods:“Zeus and ye other gods, grant that this my child may likewise prove, even as I, pre-eminent amid the Trojans, and as valiant in might, and that he rule mightily over Ilios. And some day may some man say of him as he cometh back from war,‘He is better far than his father’; [480] and may he bear the blood-stained spoils of the foeman he hath slain, and may his mother’s heart wax glad.” So saying, he laid his child in his dear wife’s arms, and she took him to her fragrant bosom, smiling through her tears; and her husband was touched with pity at sight of her, [485] and he stroked her with his hand, and spake to her, saying: “Dear wife, in no wise, I pray thee, grieve overmuch at heart; no man beyond my fate shall send me forth to Hades; only his doom, methinks, no man hath ever escaped, be he coward or valiant, when once he hath been born. [490] Nay, go thou to the house and busy thyself with thine own tasks, the loom and the distaff, and bid thy handmaids ply their work: but war shall be for men, for all, but most of all for me, of them that dwell in Ilios.”

Projekttitel: eManual Alte Geschichte

Modul [optional]:

Autor_in: Agnes von der Decken

Lizenz: CC-BY-NC-SA

Der Abschied des Hektor

Leitfragen:

1) Fassen Sie den Inhalt der Quellenpassage zusammen.

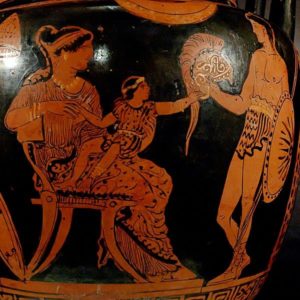

2) Vergleichen Sie die Beschreibung der Verabschiedung bei Homer mit der Vasen-Darstellung.

3) Welche Hinweise auf das Schicksal Trojas finden sich in der Quellenstelle?

Kommentar:

In dieser Passage aus der Ilias Homers wird die Verabschiedung zwischen dem trojanischen Prinzen Hektor und seiner Frau Andromache beschrieben. Andromache ist in Sorge um Hektor und die Trojaner mit ihrem Sohn Astyanax und einer Dienerin auf den großen Turm gestiegen. Hier, hoch oben über Stadt und Schlachtfeld, findet Hektor sie. Die angeführte Quellenpassage setzt an dieser Stelle ein. Andromache fleht ihren Mann, um der Familie und ihrer selbst willen, an, nicht in den Krieg und insbesondere den Kampf gegen Achilles zu ziehen. Für sie sei ein Leben ohne ihren Mann sinnlos, zumal sie nicht einmal mehr Familie habe, da Achilles schon ihre Brüder und ihren Vater getötet habe. Hektor entgegnet jedoch, dass es sein Stolz und seine Abkunft nicht zuließen, sich vom Kampf fernzuhalten. Zugleich versichert er Andromache, dass sein Tod rühmlich sei und dieser Rum seinen Tod überdauern und seine Witwe trösten werde. Daraufhin verabschiedet er sich zuerst von seinem Sohn, für den er bei Zeus um eine glorreiche Zukunft bittet, und daraufhin bei Andromache. Für sich selbst sieht Hektor den Krieg als Aufgabe, Andromache solle sich stattdessen im Haus um die Geschäfte kümmern.

Die berühmte Abschiedsszene zwischen Andromache und Hektor findet sich dargestellt auf einem rotfigurigen Krater aus Apulien aus dem 4. Jh. v. Chr. (etwa 370-360 v. Chr.). Zu sehen ist Astyanax, der auf dem Schoß seiner Mutter Andromache sitzt und nach dem Helm seines Vaters Hektor greift. Die Darstellung spiegelt dabei die literarische Vorlage bildlich wieder: Bei Homer wird genau beschrieben, wie Astyanax aus Angst vor dem glänzenden Helm und dem Helmbusch des Vaters an die Brust der Mutter zurückschreckt. Erst als Hektor den Helm lachend abnimmt, kann er seinen Sohn umarmen. Diese besondere familiäre und private Szene kurz vor dem endgültigen Abschied des Vaters und Ehemannes von seiner Familie zeigt die rotfigurige Vase. Verabschiedungsszenen wie diese, insbesondre zwischen einem Soldaten und seiner Frau, finden sich häufig als Darstellungen auf Vasen aus klassischer Zeit. Hier zeigt sich, wie ein literarisches Motiv in das Bildprogramm der Klassik übernommen wurde.

In der hier angeführten Abschiedsszene zwischen Hektor und Andromache ist eine dunkle Vorahnung auf den Tod Hektors erkennbar. So kann etwa Andromaches Aussage, dass Achilles schon ihre Brüder und ihren Vater getötet habe, dahingehend gedeutet werden, dass auch Hektor bald durch Achilles den Tod finden werde, da Andromache in Hektor Vater, Mutter und Bruder zugleich sieht. Doch ist Hektor von Andromaches Angst keineswegs verunsichert. Er ist stattdessen selbst davon überzeugt, dass der Tag, an dem Troja untergehen wird, irgendwann kommen werde. Auch ahnt er, dass er im Kampf gegen Achilles sterben wird. Er zeichnet das Bild einer Zukunft für seine Frau und seinen Sohn, in welcher er selbst nicht mehr am Leben ist. Der Abschied von Hektor kann zugleich als Vorausdeutung des Untergangs von Troja gesehen werden.